Your child is asked to work on his or her speech sound at home. Straight up drill work is not always fun for our rambunctious little kiddos and probably the last thing they want to do when they get home from school is practice their speech sound. Here are some fun ways to incorporate play into their speech practice, and they’ll be having so much fun they might just forget they’re actually working on their sounds!

You know those toy plastic bowling pins and balls? Those are GREAT to incorporate into speech practice, plus it gets your child moving. If you don’t have those, you could always use those Puffs snack containers or something similar. When I was doing therapy, I’d “bowl” with my kiddos. I’d take artic picture cards (ask your therapist for copies, or you can find pictures online targeting your child’s sound) and tape them on the pins, one-two per pin. Then take turns rolling the ball and knocking over the pins. This would be a great way to incorporate the siblings too. Have your child say the word on the picture of the pin that gets knocked over. Odds are they will get lots of practice because they will probably want to keep bowling!

Take a few minutes and take turns hiding the artic pictures around your house. When you find the picture, say the word. To kick things up a notch and make it even more interesting, you can always dim the lights and have your child use a flashlight to find the pictures. My kids at work always felt so important with their flashlight, like some kind of investigator or something.

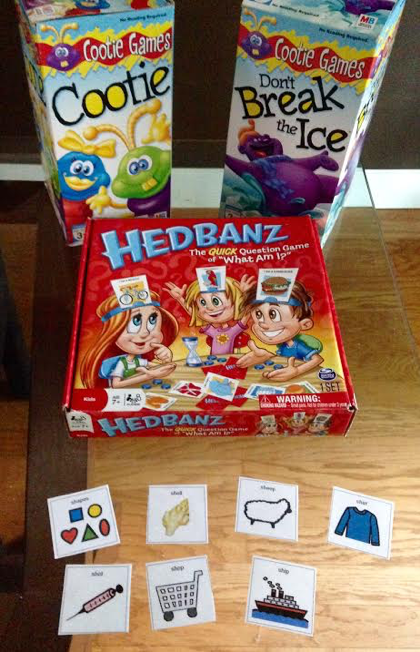

Does your child like to play games? Incorporate their artic into the game! Have your stack of cards and before your child takes a turn (or even every other turn), they need to say their word five times.

Maybe you are out at the grocery store or running errands somewhere. Have your child think of as many words as they can that start with their sound. So, say they are working on /s/ and you’re at the grocery store. They could say “sandwich”, “salad”, “soup”, “soda”, etc.

Included in this blog is a free /p/ sound printable! You can grab that here. It contains 36 playing cards and targets /p/ in the initial, middle, and final positions of words. Maybe your child is working on /p/. Maybe they’re not. Either way, keep checking back on my site for more free printable sound cards and maybe you will find the sound your child is working on!

When I assess a child’s speech, I not only look at his or her articulation errors but also their sound pattern errors. As children learn to talk, they use these patterns of sound errors called phonological processes to simplify speech. For example, you might hear your child say “da” for “dog”, “geen” for “green”, or “dob” for “job”. They do this because they can’t coordinate their articulators (lips, tongue, teeth, palate, and jaw) for clear speech. They often simplify the adult model by substituting sounds that are in their sound repertoire for sounds that they haven’t yet mastered. There are many different patterns of simplifications or phonological processes.

What’s a phonological disorder?

These processes are totally normal unless they continue beyond the age when most typically developing children have stopped using them. An example would be if your 4 year old deletes the ending sounds on words (“toe” for “toad”), which is the processes of final consonant deletion. This would be considered delayed because we expect children to stop using that process around 3 years of age.

Check out my phonological process chart which describes each process and provides an approximate age of mastery by downloading it here. (INSERT PDF HERE)

So, how can I tell if my child has a phonological delay or disorder?

If you have concerns, be sure to get your child assessed by a licensed speech-language pathologist (SLP). He or she will evaluate your child’s speech using a standardized assessment. Some red flags to be on the lookout for include:

1. How intelligible is your child?

When children use an excessive number of phonological processes, a phonological disorder is highly likely. If they delete final consonants (“be” for “bed”), delete cluster sounds (“poon” for “spoon”), stop sounds (“poo” for “zoo”), etc. their intelligibility is going to suffer. By the time a child is 2 years old, they should be about 50% intelligible to others. When they are 3 years of age, the percentage increases to about 75% to an unfamiliar listener, and by 4-5 years they should be approximately 90-100% intelligible even if they still have a few articulation errors.

2. Are they deleting initial sounds of words?

The phonological process of initial consonant deletion is not a common one. If you hear your child say “up” for “cup”, “oap” for “soap”, or “ed” for “bed”, you may want to consult a SLP.

3. Is your child frustrated when someone does not understand him/her?

What happens if my child has a phonological disorder?

If your child is diagnosed with a phonological disorder and the speech pathologist recommends speech therapy, the SLP will work on the specific process or processes in error, which will help improve your child’s intelligibility. Targeting the process instead of the individual sound error as you would in articulation therapy usually helps improve the child’s intelligibility at a faster rate if indeed they have a phonological disorder. For example if I assessed a child who deleted final consonants, my therapy goal would probably look something like this:

Patient will produce final consonants on words with 80% accuracy over 3 consecutive sessions.

To target this goal, I’d probably use minimal pair (words that differ in only one phonological element) picture cards like go/goat, bow/boat, bee/beep, etc. and have the child first identify the pictures to see if they can hear the difference and then we’d work on production. After laying out a pair of cards, say the pictures of “go” and “goat” in front of the child, I might say, “Ok Johnny, you tell me which picture to point to.” Then I’ll point to the picture he says. Obviously if he deletes final consonants, he’d probably say “go” for “goat” but then that is where I’d show him what to do to produce that final sound and say “goat”. You want the child to understand that when they say the sound incorrectly (or omit a sound), it actually changes the word’s meaning.

Well that’s phonological processes in a nutshell. Again, if you have concerns about your child’s speech, please consult a SLP near you!